Zooming In Zoning Out

In a rather mediocre film from the early 00’s, Kevin Spacey’s character, an American university professor lecturing freshmen, states: “You get Lacan’s point? Fantasies have to be unrealistic, because the moment, the second you get what you seek, you don’t, you can’t want it anymore. In order to continue to exist, desire must have its objects perpetually absent.”

Desire associates, through Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis in general, with lack. An unfortunate relation as it implicitly proposes that you can only want something that can be identified, which means that desire consolidates the world as we know it. Desire from this point of view is normative, and in addition, the perspective is excellently compatible with modern day capitalism, or perhaps psychoanalysis created the perfect conditions for societies based on supply, demand, production and consumption?

Related to work, domestic labour and general maintenance of society, for Freud desire is understood as an anomaly, a disturbance or bump in the road that the individual is assumed to deal with efficiently and swiftly get back to work.

Others have argued against lack and instead proposed that desire is a form of, although soft, machine that generates forms of change. Desire as productive imbalance or rhythmic irregularity that most of the time is resolved through conventional means but at times end up producing breaches, collapses of the symbolic order and forces a re-articulation of reality and the world. Lack oriented articulations of desire are at the end of the day a concern about property and ownership, whereas desiring machines implies that making oneself available for desire equals becoming vulnerable, putting oneself at risk. The dynamics of psychoanalysis identifies desire as private and engaging with it as acts of privatisation. Desire understood as a machine instead are engagements with becoming public, or common, thus encounters with desire unsettle the subject, making it a productive availability that offers or forces the individual to generate a decision instead of simply making a choice between accessible alternatives.

*

A girlfriend once told me that she just wanted to care for me. Chatting away on the couch of my psychoanalyst years later I realised that that was the moment I left her.

One can generally identify two forms of care. Care for something or somebody; directional care is crucial to conduct and share life but in being directional it cannot not be charged with value, expectation, debt, gratitude etc. In short, conventional forms of care although given with heart and soul are always an actual or symbolic economic form of exchange. Care’s relationship to desire is evidently complex, in particular relating to lack alternatively being unsettled.

A different form of care has by the philosopher Karen Barad been named indifferent care. It’s care “given” for no reason, without expectations or other investments, the problem is just that it’s a kind of care that cannot be practised in societies grounded on a capitalist mindset, Christian theology, private property and so on.

“We can try, maybe it can be a little indifferent,” but no and a little bit of indifference is certainly not an option. So why if impossible is indifferent care important? Because it doesn’t determine an outcome, it doesn’t support or dismiss anything, which is how its outcome is contingent on its practice, contingent also, according to Barad, to the individual being cared for. Conventional, direction care is not farfetched to align with lack. Many forms of care suggest catering for the needs, wishes and desire of the cared for, which when exaggerated can result in apathy. Indifferent care instead opens up for desire as generative, as a machine that can be engaged partially because of the “safe” space offered through care.

The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben is not using the notion of indifference but indicates similar strategies. Whatever, he argues, has not always signified a lack of care, indifference in the negative sense, “as if could care,” but did in the Roman tradition rather imply whatever it is is always of importance. Referring to love, Agamben proposes that although you might not agree, to love means whatever it is is always of importance. Whatever or indifference equals the absence or suspense of judgement, value, expectations, payback or debt in favour of being attentive to whatever it is. We must just not forget that this form of attention is incredibly demanding and makes the person particularly vulnerable. Love implicitly is a deliberate engagement in making oneself weak.

*

Repetition is ordinarily understood as a means of perfecting something. The familiar: after decades of devoted practice the artist managed in one brush stroke to capture the rooster’s essence. An almost Confucian attitude suggesting that fulfilment or perfection is verified on the basis of established regulations, and hence conceive of essence as a stability, coagulation or permanence.

In regard to so-called conceptual repetition the concept, in this case the rooster, remains identical and each drawing differs only in degree, hence they can be compared and considered for example in respect of level of success. This kind of repetition is a reiteration of the identical, however, what happens when repetition is situated instead at the level of the existent? When what is repeated is not the same but something different, this rooster, that rooster, another rooster, some rooster etc., thus moving not in the direction of essence but particularity. Here, comparison is not excluded but rather than forming a kind of statistics what occurs is how comparison or value is always violent. Instead of considering repetition in regard to fine-tuning, perfection or essence, non-conceptual repetition proposes a strategic, however indifferent, departure from judgement, consistent with Agamben’s whatever, Barad’s indifference and a post-Freudian comprehension of desire, desire as an apparatus generating indetermination.

*

The imaginary of the sexual revolution of the 60s and 70s assumes that people had a lot of sex all the time. The narrative created regarding free or liberated sex appears in hindsight naïve and to predominantly reflect quantitative levels. A more rigorous consideration would be not just to take “advantage” of a novel liberty, so to say more of the same, but instead examine both the sex and free part with the possible result that free doesn’t necessarily mean more but differently, even contingently different. It’s not the “user” that needs to be freed, it’s sex and how sex is political and practised in relation to power, institutionality and accountability that must be reconsidered and possibly freed.

Freedom from and freedom to, all good but it’s still free in respect to something, for example some kind of lack. Perhaps it’s needed, in relation to desire, care and artistic practice to examine freedom not in the direction of “right” but instead as a zone in and during which conditions are suspended.

Contemporary popular ecology is often suffering from a similar naïve narration. Not only will humanity fix it but without considering how we are humans and inhabit the planet. It’s the world that’s supposed to be saved, our world, not the earth, and the planet is rarely taken into account. Humans without further questions entitle themselves to be in charge seemingly having no problems with the possibility that there are creatures and other capacities on the planet that have no interest in saving the world as we know it, but are happy to move to the next level. And from the perspective of the planet humanity might not even be worth mentioning considering the bigger picture. Zoom out and humanity is nothing more than a mishap, a moment’s irritation like when you hesitate for an instant before recalling your password.

It’s evident that no other species, in fact nothing else, has managed to out-strengthen nature and tip the balances of our planet, or the powers labouring on the crust of Terra Firma. So, although quite uncomfortable, the first thing to fix is not the planet or earth but humanity. The problem is that humanity cannot transform in any prominent way through conventional tools because as much as we made the tools, the tools also made us, and one of those tools is imagination. The worlds and conditions humanity can imagine might be weird, scary or utopian, but they are still and cannot otherwise be constructed in regard to the mindset of our presence.

Politics, argues the French philosopher Jacques Rancière, first and foremost is the maintenance of the police, our society. Right or left wing is different but in principle, the job is to sustain and enhance living conditions. Politics’ first responsibility is not to generate change but to keep up and household with what we have, but does that not also mean that politics is powerless in respect to transforming in any prominent way our relation to the world, the earth and the planet, even to ourselves? If politics primarily is a matter of managing and protecting it also means concerning the subject. In conclusion, politics consolidates how humanity relates to the world.

*

No art whatsoever escapes being co-opted by capitalism. There’s no way out since the omnipresent global market economy simply is the foundation of experience, value, exchange and participation. But, what if in parallel art also is a machine with which the viewer, reader or listener engages and is entangled with? The art machine, however, is not a conventional machine such as toasters, toothbrushes, a forklift, map or search engine, because contrary to other machines the artwork/machine has no purpose except being and performing artwork. Its objective is not to implode meaning into an abstract void of empty signifiers, but the concern of intention concerning an artwork degrades it to the futile task of fulfilling a function instead of being an open-ended exploration. It transforms the artwork into a design object, and it would be ridiculous, although not unusual, to critique an artwork for how effectively it concluded its function or to consider its reliability. Artwork/machines bypass probability, the likelihood of something’s occurrence, in favour of contingent outcome, which cannot be considered a result but implies the possibility of the emergence of something previously unthinkable. Contingent outcome and the art machine introduce a realm that’s beyond although not excluding what is possible and impossible, in other words, what can be identified and sanctions potentiality.

Commensurate, the difference between the production of another one, another ballpen or even a new iPhone (after all it’s just another phone) and bringing something into the world, the production of something altogether otherwise. A complex consequence for good and bad, the price to pay, is that the artwork/machine cannot control what emerges, and even more interestingly neither the artist nor the viewer can know what the outcome indicates, signifies or simply what it is. A discrepancy opens between appearance and what it is, or the artwork is a smokescreen or pathway into engaging with the machine.

Under those terms the artwork/machine does not equal, at least not only, forms of representations of the world, mimesis, imitation, metaphor, symbol etc., but grants art the capacity of making or even creating worlds, small, big and overwhelming. In parenthesis, albeit significant, the artwork/machine doesn’t only generate contingent outcomes but is also contingent to itself, ensuring that each engagement is singular, and that contingency doesn’t coagulate into probable outcome.

*

It’s conventional to distinguish between two forms of forgiveness. Certain things are already and others cannot under any circumstances be forgiven. You miss out on opening the door for somebody and the apology is accepted before you open your mouth. There are also occurrences that must not be forgiven, because, as we know, to forgive is to forget. Genocide is a used example but unforgiveables are not about size but irreversibility. Importantly, they have nothing to do with payback or revenge, nor with the insurance of not forgetting but about insisting on keeping something open, of not transforming the act into a thing or object but insisting on keeping it open, a happening, a form of machine.

Without comparison perhaps there are also two kinds of kisses. The ones on the cheek or when departing from a lover, partner or spouse, all those whose meaning is already established before, during and after they are executed. They are deliberate, nice, confirming, largely without consequences, alas they operate within the realm of the probable. Then there are those rare ones, really rare, the ones to which the outcome is contingent, those that take place a millisecond after surrendering oneself to the possibility of absolute irreversibility, of being totally blown away, catapulted to another world or, simply, getting genuinely fucking lost.

At that moment the kiss is not a thing but a machine producing the future. Not a future that relies on lived experience, not a projection of the past into what is to come, but a future without conditions. And mind you, this form of being lost isn’t like being lost in a city, forest or desert, it’s being lost in regard to oneself, self-referentially lost.

20 March 2024

Mårten Spångberg is a choreographer and writer living and working in Berlin. During one year, he will contribute with monthly columns on dance, aesthetics and politics.

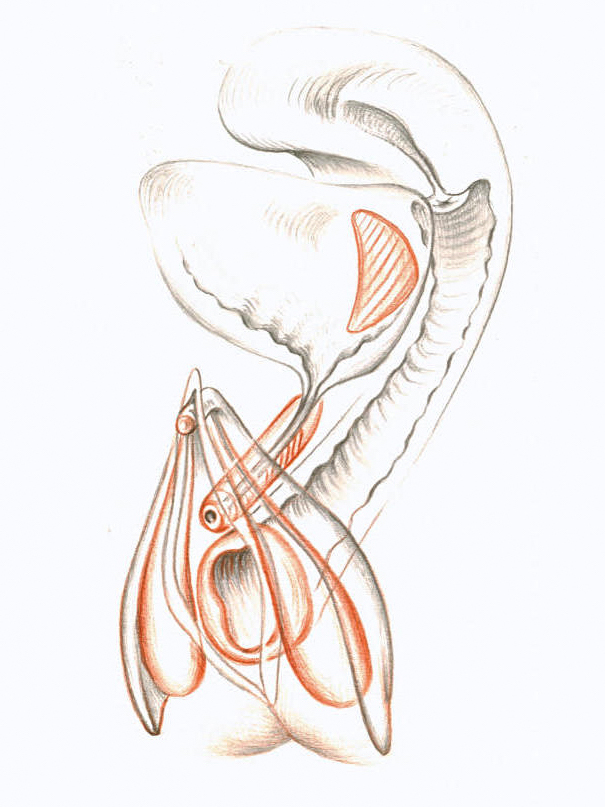

Alejandra Pombo Su is a multi-disciplinary artist living and working in Santiago de Compostela. Grounded in performative practices her work extends into poetry, film, sculpture, drawing and painting, energised through a drive to simultaneously embrace and deterritorialize established formats, thus addressing, for example, painting at once both as concept and ecology. Precisely articulated procedures, often including repetition, produce active resistances to intuition and expression, unfolding landscapes in which appearance and being, identity and body, enunciation and magic blur vision and apprehension.

For the coming twelve months, Alejandra Pombo Su will create associative portraits accompanying the columns by Mårten Spångberg. The portraits further function as one node in a shared research project into the performativity of portraits in times of biometric monitoring and advanced eye-tracking technologies.

This or That but Never a Little Bit.

It’s curious how the English language has been gifted with both freedom and liberty, whereas other Western languages have had to choose only one. One can wonder if Brits, Americans and related are so desperate they need two terms for the same thing, or if the double shot makes them twice as free and liberated? The French who sort of introduced the notion can fiddle around with liberty but are cut off from freedom, whereas the Germans struggle with the opposite, freedom but no liberty. Who is best off, liberté ohne Freiheit, or Freiheit sans liberté? Beats me, but there’s probably some cute etymological explanation although I have personal issues with writers, scholars and don’t mention philosophers who bring up or reference some or other notion’s back story. Don’t ask me why and I’m of course full of prejudice, but to me, it’s simultaneously patronising and expressing a lack of elegance.

The French philosopher François Laruelle has somewhere proposed that there’s a significant difference between liberty and, as the translator somewhat clunkily phrases it, liberty’s rigour. A rigorous engagement with liberty is considerably more difficult than with liberty itself, writes Laruelle, in fact, it’s an altogether different story and might generate distinctly other outcomes.

A stupid example: consider that you’re driving your car on a road with speed limits, easy going no problem. You are at liberty to traverse the landscape as you see fit as long as you don’t exceed regulations. At some point, a sign announces, “end of all speed bans,” a white circle with five black diagonal lines. Pedal to the metal, the highway has been liberated from limitations regarding velocity and you’re at liberty to chauffeur your vehicle at any speed. A conventional understanding of liberty, suggests Laruelle, implies that the new or revised situation operates as an extension or expansion to the previous, or the two conditions are causal to each other, their relationship is probabilistic. In short, I will drive faster because I can. More importantly, however, is that liberty here is contained, in the sense that nothing else is provoked or transformed except the end of all speed bans. There’s no ambiguity, it’s rudimentary, relations are linear, drive faster, that is, the grounds upon which observations or decisions are made remain stable and thus don’t exceed the domain of strategy.

A rigorous engagement with liberty turns the affair on its head, refuses compartmentalisation, divisibility and probability and instead asks, what on a structural or fundamental level cannot not change given the altered circumstances? For example, what happens to the understanding, even ontology, of speed if its limits are banned?

Liberty’s rigour comprehended as a practice indicates a sensitivity to all other possible and impossible consequences that the end of all speed bans opens for. In other words, liberty’s rigour fucks causality and probable outcome and favours contingent, stochastic, non-calculable results that as much as they might be ordinary simultaneously can short-circuit the very conditions of the world.

When considering freedom, it might be valuable to identify two general forms. On the one hand, what one can call constituted freedom, which largely aligns with Isaiah Berlin’s elaboration of freedom from and freedom to. Freedoms that are given and protected, normally, by the state. For example, the state offers all citizens, without exception, the opportunity to move freely in, let’s say a city and protects that freedom or right if infringed upon. You are also free to drive a car in the city but the authorisation is valid only with a legitimate licence.

So, when an American dude exclaims, “Free country, huh!” it’s obviously not free at all, it’s only free with respect to what the constitution, government and, in the case of the US, mostly too old and too rich gentlemen have agreed upon. Simply put, the price to pay for this kind of freedom is paying your taxes, which makes it somewhat paradoxical to encounter that individuals identified as freedom fighters oftentimes have something personal against taxes. The other way around appears smarter, taxes, another word for the state, secure our freedom, not just mine but everybody’s. The problem is perhaps that everybody’s isn’t part of those guys’ vocabulary.

Come to think of it, the free country thing almost without exception resonates with an extractivist mindset, a settler-colonial tonality and an individualistic abusive attitude. I do what I want and nobody has the right to hold me responsible for whatever that is or was. “It’s a free country, huh.” Yeah, sure but only for certain authorised populations, right? Seriously, all those cowboys and whatnots are so annoying, that kind of freedom when considered properly is at the end of the day synonymous with responsibility, or perhaps a society that shares this understanding is what we call, with an at times infected word, civilised?

Freedom in this sense shouldn’t be dismissed on the contrary it’s fundamentally necessary to conduct life, establish relationships, control violence and manage any form of community or society. It’s perhaps also a bit rushed to argue that people are living a lie being manipulated by some all-seeing eye or machine. People know it, it just makes shit way easier ignoring it. I mean who didn’t roll their eyes the day Magritte revealed it’s not a pipe or when The Wooster group broke the fourth wall? Been there, done that.

The second form of freedom, freedom that is void of any form of authorisation is much less complicated but simultaneously impossible to unfold and give extension in any real-life situation. Absolute freedom turns on itself and becomes totalitarian, it eradicates every form of choice, relation, change, difference and dynamics, even time, space, stability and direction. Somewhat paradoxically to prominent freedom there are no options, it’s freedom and that’s it. Absolute freedom is the antithesis of negotiation and therefore the obverse of politics, after all, absolute is not a different way of saying a little bit. Keep in mind, if you for some reason bump into a genie, think twice before you wish for freedom, because freedom the real deal isn’t like a cabin in the forest, a bottle of bourbon and a golden retriever. For starters, freedom cannot be shared, freedom has no friends and isn’t a society. The image of freedom and feeling free is far from being free.

*

Art is not culture nor is culture art. Culture and art are differentiated in respect of value. Culture is known, negotiated, measurable, comparable and attached to value similar to any other service or commodity. Art grasped as a thing or object follows similar if not identical dynamics but the artwork as artwork and aesthetic encounter is a different story. In order to contextualise a specific artwork’s value, which naturally is provoked and dependent on forces that want to make profit but not exclusively, a different set of strategies must be applied. The value of an artwork, a painting, a theatre performance or a novel, cannot be reduced to a calculation of labour hours, costs for materials, rent and transportation before anything else because material value is not all there is, but more centrally, only regarded as singular can the artwork circumvent being synonymous to its functions, and if value is accounted for in regard to function any reproduction of Mona Lisa would be equally fine, as much as any Iphone 14 is equally Iphone14.

But if the artwork exists in its own right, it cannot not be void of value, value after all is constituted through forms of comparison.

Culture follows the logic of constituted freedom whereas art, in respect of its status as artwork, aligns with the absence of the logic of prominent or absolute freedom, which furthermore allows us to pair the artwork’s singularity, which mustn’t be mixed up with individuality or uniqueness which remain relational capacities, with sovereignty.

Laruelle asks, how can one conceive of the principles of liberation without immediately unleashing fantasies of total freedom and anything goes? Without trying to answer, it’s not crazy to connect culture and cultural work with liberty, the easy way, and art with liberty’s rigour. The artistic labour or aesthetic engagement, differentiated from accompanying craft and managerial labour vis à vis which the artist is identified as a cultural worker, denies itself the opportunity to take advantage of liberty and is instead driven by rigour, without which aesthetic engagement would stumble precipitously into exactly fantasies of total freedom and anything goes.

From this perspective, artistic freedom has very little to do with freeing oneself, being or feeling free, or offering the opportunity to express whatever one wants. On the contrary, artistic freedom, independently of medium, format, alone or together, instead indicates the opportunity to engage with liberty’s rigour and hence the outcome of such engagement cannot be determined it cannot not be anything else than freedom, the freedom of not being able to anticipate a result, effect or ramifications. Said differently, artistic freedom implies the authorisation of being irresponsible, which evidently is a massive responsibility.

But wait a second, don’t forget that this freedom is exclusive to artistic labour and the aesthetic engagement, and doesn’t authorise anybody to be a douchebag, take advantage of people, be generally flaky or whatever artistic anything goes behaviour.

*

Autonomy is something that has haunted art and its discourses for more than two hundred years. Contemplating or appreciating an artwork, argued Kant, must be an autonomous activity freed from interests, and for this to be possible, the artwork must also be understood as autonomous. The artwork doesn’t need support or back-up and its value is not dependent on its relations. Needless to say, every artwork needs support in the sense of a stage, a plinth, a wall, a screen, a photo album, a storage space, a bookshelf or museum but again this is the object or activity which isn’t synonymous with the artwork.

The artwork’s and the aesthetic encounter’s autonomy is, however, particular and constructed otherwise than the autonomy of say a body, a nation, a process or forms of decision making, which can cause some confusion. Conventional forms of autonomy are relational and established through arguments, division and borders. A body is autonomous through, for example, a social security number, a name or the opacity of the skin, but it’s still comparable, divisible and exchangeable. Something is autonomous because of what it’s not. More examples, France is not Norway or the process of creating a dance performance is autonomous to baking a sponge cake, still, we understand something’s autonomy only in regard to other similar entities, other nations, dances or cakes. Autonomy in the sense of talk to the hand, and since it’s based on “not that” it can or must be defended.

The artwork, and possibly a few other opportunities, flipside or reverse the terms. Autonomous due to something’s singularity implies that it cannot establish relations and is unable to generate borders, after all, how do you build a border to nothing? The artwork’s autonomy has zero to do with what it’s not, rejection or provocation but on being unconditionally defenceless and totally open.

A body or nation’s autonomy is authorised, if only through “not that,” whereas the artwork’s is absolute. One could also say, conventional autonomy is effective and the artworks and the aesthetic experience autonomy affective.

*

Freedom of speech or expression and artistic freedom are not rarely equated, put in the same basket and used, especially by the populist right, as a means to bash interventionist cultural politics in favour of assumed self-regulating market-oriented financial support, philanthropy, patronage and similar. The argument, in short, is that all forms of state-regulated cultural politics infringe on the freedom of expression resulting in instrumentalised art, art as a service for the state apparatus and ultimately malign censorship. Unfortunately, the jargon of the right has slowly and tenaciously infected the entire debate concerning cultural politics and the social democratic left has, instead of taking a stand-up position putting up a struggle, among other passive-aggressive concepts introduced arm’s-lengths distance in order to shield art, or culture as is the favoured term is, from meddlesome politicians, or as the far right warns from ultra-woke identity politics.

An initial problem is the strategic blending of art and culture whose aim is to correlate artistic quality and cultural value. This process favours value and relativises quality, using the argument that value is quantifiable and therefore measurable, we can understand and “prove” what it’s good for, whereas quality, WTF is that supposed to be good for? On a practical level, and this is really worrisome, it moreover proposes that there’s no categorical difference regarding engagement – social, political, financial, concerning identity, accessibility etc. – between a museum director, a graphic designer, a game show host and a dancer, painter or novelist. Evidently, both museum staff and installation artists work within the cultural sector but what they produce, may that be an activity in the case of a tour guide or a dancer or a material object created by a painter or a wig maker in a city theatre, are principally different, even ontologically exclusive.

A museum director who offers a blockbuster show for the tourist-intense summer months, fair enough I get it, but a painter who jampacks canvases with puppy dogs and fluffy kittens as a means to cater to the vulgar taste of potential clients comes across as compromised. The problem isn’t paintings with baby animals, but when an image’s motif is directional to a business plan the work is reduced to its function.

Reversing the dynamics, the director of a dance festival is responsible vis à vis an audience and can invoke it arguing for the composition of the program. As a cultural producer, the artist is also responsible, for example deciding not to show depictions of violence for a young audience, but isn’t regarding the choice of motif, abstraction, figurative, excessive violence or puppy dogs. There’s a significant difference, recalling Laruelle, between what somebody paints and what that somebody decides to show. Yet, there isn’t a significant difference between what a museum director decides to exhibit and what the audience is shown.

Regrettably and thankfully, in practice things are not that water tight cut but liberty’s rigour might still not be a bad idea.

Freedom of speech appears today to have become somewhat one dimensional, lost track of reciprocity and responsibility, and through the acceleration of right-wing rhetoric transformed into something like: Anybody has the right to say, write or express whatever they want and if there are any consequences the individual should be protected without regard for or not taking responsibility for what was expressed. To me, that sounds approximately as mature as a punk shouting fuck the police with a raised middle finger but calling 911 when being evicted after months of unpaid rent.

Freedom of speech is an authorised form of freedom – the state grants each individual the right etc., but like any grant, the price to pay is that you’re obliged to report how it was used.

Artistic freedom occupies an entirely different territory. It doesn’t authorize the right to express whatever you want but instead, the opportunity to express something you don’t know what it is or what it expresses. The price to pay is that since what is expressed is not known it can also not, except on a strictly structural level, be protected. But mind you, this is by the same token what makes art exceed arguments and convincing rhetoric in favour of the fantastical, overwhelming and goddamn world changing.

16 February 2024

To Itself as Itself

At a dinner party somebody responds, “Yeah, but however much money, you’d still be looking for a good deal.” The conversation ricocheted and I never grabbed the chance to voice whatever position, but to me it’s obvious, the only interest in economic wealth is in order not to have to bother about money. Rich I couldn’t care less, what matters is economic independence, in short using zero energy on the status of my savings account.

Money, thinking about Heidegger’s tool analysis, is always broken, and can simply not hold itself from reminding us of its toolness. To possess money implies, if not to overcome Heidegger at least to have your money fixed and repaired, hence having the opportunity to take it for granted.

It’s of course possible that “good deal” extended beyond moolah, but even if it did, what sadness to conceive of life as a series of good or best deals? Isn’t that the equivalent to swapping desire for revenue, joy for appreciation, friendship for tolerance? By the way, if good deals were my life-style choice, devoting my short time on earth to dance appears rather ridiculous.

*

The Americans feared losing aeroplanes to the other side of the Cold War. The Russians, they argued, and probably correctly, would salvage aircrafts and perform reverse engineering as a means to obtain American technological prowess. One can wonder what Heidegger would have to say about the exchange and what happens to the analysis of tools when taken apart to the tiniest component. Evident, and the stipulation of said practice, in any case, is that there’s analogy between part and whole, that the individual component relates to the entirety through causality, and that value is linear and determined from atom to the complete apparatus.

*

At some point, Zaha Hadid questioned why architects for centuries have been obsessing about 90-degree angles. “Why only one angle, when there’re 360 degrees to choose from?” Radical? Not exactly. After all, it’s still just degrees. Anything other than 90 might just be considered trying to be special.

Some say, and Hadid obviously agreed, that the horizon equals the sum of possible perspectives. All perspectives next to each other, one after the other and abracadabra: horizon. Fortunately, the relation between perspective and horizon isn’t part to whole, causal or linear, and the value of horizon isn’t the sum of perspectives. Horizon, which is definite although without article isn’t synonymous with the horizon, which is what you look at on the beach, is precisely the absence of the possibility of perspective.

Horizon is one, it cannot be divided and hence it cannot be introduced into any system of value, which without exception is based on divisibility. Stuff that remains one, such as the universe, nothing, magic, or love (at least for some) withdraws from conventional forms of value and is valuable in regard only to itself as itself, its value is self-referential. Or whatever value experienced is supplementary to the thing, situation or phenomenon. Supplementary in the sense that it cannot be extracted or located in a certain part, that there exists no causality between what is mediated and what is experienced.

*

Analyses and interpretation are based on identifying and locating, on dividing and extracting and hence on being able to determine value through relations between parts and whole, for example through comparison and measuring. Value moreover, however much it struggles, cannot withdraw from hierarchisation and power, reason and rationality, from making good or best deals. Anything that can be introduced to a system of value consolidates that system. Analyses, reason or good deals in other words reinforce representation, knowledge, power and general fuckery as we already know it.

Horizon, on the other hand because it’s self-referential, is one, cannot be subjected to comparison or measure, cannot be captured by reason and most importantly transcends hierarchization and power, which at the same time renders horizon powerless and autonomous.

I like to think that art, no in fact I’m convinced that spending time with art, making or attending art, the experience of art, carries the promise of horizon. Those few but irreversible encounters with art are overwhelming and irreversible exactly because the value of the experience is supplementary to what, so to say, caused it, that there is no causality between the artwork and what the time spent with it generates. Similar to horizon, those rare encounters with art refer only to themselves as themselves and are therefore autonomous, but remember, it’s the encounter that’s self-referential, not the artwork. It, whether abstract or not, narrative or not, dance, poetry or installation is irreversibly attached to perspective and value. Perhaps the opposite of a good deal, which is synonymous with being in control, is losing one’s shit and being blown away.

*

On the back cover of a brand-new novel, I forgot the title, picked up in an oh-so-urban alternative yet corporate bookstore, I read, “a depiction of a utopian micro-society, an attempt to live in mutual tolerance and freedom.” Seriously, I’m starting to develop unhealthy reactions to utopia, especially its use in relation to art and artistic projects.

Utopia, if not just borrowed from sci-fi pulp, isn’t some idyllic meadow where children play and grown-ups practice harmony with nature, each other and everything else. It’s not somewhere inhabited by mindful vegetarians that respect all and everybody including cancel culture, and by the way, does utopia include other species, historical injustices, minimal wages, lithium batteries and one-click buying, or is it maybe just for humans, perhaps only some, the nice ones?

Let me tell you, utopia isn’t a nicer form of liberal democracy where everybody lives according to their individual wishes and dreams. How could it be? It wouldn’t take long before those wishes and dreams crashed into each other and we know what happens then. What does utopia do with people who enjoy conflicts, and me who suffers from conflict trauma?

Of course, we know that utopia is unobtainable and at best a vision but even so, it’s not a political strategy that can be applied to representational democracy. It’s an entirely different political structure, actually, it’s not politics in any respect because, as the French philosopher Jacques Rancière has taught us, politics is the manifestation of dissensus. Politics, not dystopia (whatever that now might be), is the obverse of politics, exactly because conflict, perforce, is non-existent.

The implementation of any political system, any form of governance, is inevitably totalitarian. For example, from now on, democracy for all. There can’t really be any exceptions, and every political system’s first incentive is to preserve its totalitarian capacity or eradicate anything or -body that isn’t included in “for all.” On a positive note, it’s that initial totalitarian implementation which makes politics possible, that offers a ground upon which to disagree, to have wishes and desires, practice difference and diversity, to struggle, suffer or simply live. Utopia is no exception; the crux is just that it’s nothing else than totalitarian, all the time and in every respect, 24-7.For utopia to fulfil its promises of an ideal world the price to pay is the erasure of any form of difference, including desire, wishes, love interests, individuality, personal aptitude, taste in music or preference for food or sexual partners. Utopia can’t have it. In utopia, everybody is 100% identical, every form of difference or differentiation is erased, and that includes everywhere, every day and every moment. Utopia equals the extermination of difference and time, full stop.

But what about a little bit or micro utopia? Sorry, utopia is on or off, it just doesn’t do grey scale. How would that look? A bit nicer, less long days, booze without hangovers, slot machines with repeated jackpots, kids that pick up themselves from kindergarten? Great but somebody still has to clean up, hang the laundry, get fired, endure a long-term prison sentence, charge you for a pack of Marlboros at the alimentation generale or print the money?

Micro utopia? What’s that supposed to be? The little utopia experienced when I pick up the newspaper from my newly ordered Amazon letterbox, the rush when I’m told my show is sold out. Just asking? Utopia has nothing to do with feeling good or awesome, in fact, feelings of any kind are also gone.

An option in order to bypass the micro utopia issue is turning to the adjective form, utopian, but that’s obviously approximately as visionary as Zaha Hadid. It’s utopia from the perspective of liberal democracy, global capitalism, maintained forms of subjectivity and good deals, and has nothing to do with utopia.

It’s fascinating to encounter how people imagine an ideal society. More than too often it seems, at least in the West, to resemble the late 50s, except that the 70% of the workforce that was locked up in factories seems to have the day off and everybody is white, straight and middle-class. It’s never 1783 and pissing rain or Belgrade, never mind Buenos Aires on the 29th of June 1986. Our problem is that imagination is attached and dependent on knowledge, and therefore we can only create visions of utopia in regard to what we already know, from here and now. But utopia has nothing to do with imagination, instead whatever utopia could be is supplementary to imagination and is void of any causality to any world we can envision. In addition, since utopia only can exist through the eradication of difference, space and time, it must necessarily be one, and is therefore self-referential, has value only in respect of itself to itself and is autonomous.

Horizon and utopia, utopia and horizon are one and the same, and the same as one. The aesthetic experience, the encounter with art, is not utopian or like watching the horizon, but it is horizon and utopia. It’s a form of encounter that transcends space and time, that is one, has no value except to itself as itself and because it’s self-referential, and needless to be autonomous, can be nothing else than overwhelming.

6 January 2024

Stories and Landscapes

I don’t want more stories. Who decided that they are unconditionally good and that storytelling is making the world a better place? Actually, I don’t want more images either, not at all, but first stories. I wake up to stories, live them throughout the day and before turning off the bedside lamp I pass through a few stories on Instagram that the algorithm pushes in my direction. I step into a café and a story is offered to me, flat or something else white. It’s my choice but the narrative is already laid out. The choice is not mine, or mine as long as somebody else makes money. I recall that song from Shakira, “Underneath Your Clothes,” but I don’t want there to be a story. Stories determine, they predict and as much as they can be exciting and eye-opening, they are equally experts on filtering, excluding, editing out, marginalizing, unseeing and forgetting. Whatever my outfit is is evidently a story but what’s underneath, underneath wrinkles, skin colour, scars, indentations, tattoos, nail polish, shaved or not armpits, is perhaps better off remaining a geography that neither in- nor ex-cludes, that doesn’t guide, pave the way or close doors.

The Iranian philosopher Reza Negarestani in his earlier writing differentiated between openness and being open. Openness, although conventionally understood as positive, is unfailingly partial, negotiated, charged with value and hence power. The outlines of the domain of openness are without exception established by the more powerful or economically prominent entity involved. Openness is always conditioned, whereas being open, or the open, is void of conditions, it’s one and not divided, unnegotiated and can therefore not be imbued with value or power. The open makes no exceptions, lacks any form of dramaturgy and withdraws, contrary to openness that always is a story.

The world and our lives are today so full of stories it’s becoming urgent to protect zones that haven’t already been co-opted, saturated by stories. Globalised capitalism additionally strategically homogenises not just what stories “can” be told, but also their structural framework, how stories are efficiently told or otherwise passed on. There are no more stories that aren’t first of all the story of capitalism. Some say, “I need to tell my story,” but there are no personal stories, since Roland Barthes’ “The Death of The Author” (1967), every and all stories are conventional. It’s not we that tell our stories it’s stories that tell us, and “my,” in my story is evidently an illusion, which is not a problem necessarily, but good to know. The moment your story is told it’s difficult to shake it off. Your story is also the traces you leave behind, may they be broken hearts, police records or search history.

Let’s for a moment consider care practices for places, spaces, times and moments that are not yet caught in the net of stories and their telling.

Stories should of course be told, again and again, all stories. In particular, stories that have not been heard, stories about suffering, ancestry, invisibility, lack of representation, the stories of minorities, abused, enslaved, mothers, the power- and voiceless. Of course, they should be given voice, be told and passed on, but aren’t there also dangers in folding everything into stories, because they are and cannot not in themselves be efficient, linear, comprehensive and, inevitably homogenizing? Stories through their structural organisation reproduce conventional anthropocentric relations between subject and object, human and non-human, nature and culture, and most of all are masterminding binary relations between good and bad, love and hate, inside and outside.

Whatever cannot be made into a story doesn’t exist, simultaneously whatever is made into a story is nothing more than the story, and what a story is, its organization and framework, or can be, is authorized not by the storyteller but by the listeners, who obviously expect a “good” story. Stories and storytelling, although they might portray atrocities and gruesome events, are comforting if for no other reason than that they give the listener the opportunity to identify him, her or themselves, positively or negatively doesn’t matter, in regard to the story. There’s always a hero and someone is always rescued, somebody always learns a lesson or ends up on top as we learned from Vladimir Propp many years ago. Never mind the moment the story has been told, although it might reverberate within us, it can be put aside, placed in the archive and forgotten.

Concerning images this is something that the French philosopher George Didi-Huberman has problematized but there is a need to research storytelling and its effect on memory, remembrance and compartmentalisation, similar to how Didi-Huberman argues that some images must remain unseen.

At some point, the Swedish poet Gunnar Ekelöf wrote about the importance of keeping a wound open and clean. Wounds, he insisted, must not become stories but ongoing events (a duration that doesn’t develop into an extension in time). The moment a wound transforms into a story it’s fixed. Fixed but is it healed or does the trauma remain?

I don’t want more stories because they determine who we are, they force themselves upon us no matter what. I want landscapes because what they don’t do, they don’t settle, don’t draw lines or divide into binary oppositions, don’t bother about having the “weak” saved by the strong, don’t have children push witches into ovens, kings decide for their daughters, sons kill their fathers or informing our kids to stay away from strangers. Landscapes contrary to stories are indifferent. Indifferent, however not in the sense of “I couldn’t care less,” but instead “whatever it is, always of importance.” Not as a permission, which invariably implies authority, but a form of disinterestedness, that isn’t synonymous with uninterested but with withdrawing from taking side, having this or that interest. Disinterested in the sense of a refusal to judge.

*

This slight, however crucial misunderstanding indeed is messing with art and forms of aesthetic appreciation. When Emanuel Kant in the late 18th century pins down that art must be contemplated disinterestedly, although his theories can be contested, it’s of weight to interpret disinterestedness in respect of active indifference, without expectations, morals, preconceptions or judgement. For Kant the encounter with art, in other words, is not about openness but of being open, it’s an engagement with a terrain or landscape and so not with stories.

But we object, what about novels, theatre, opera, short stories and pop songs, absolutely but, at least with the Kantian canon the story, whatever it is, is just a smokescreen, a little bit of seduction to enter the real deal, aesthetic appreciation. If this wasn’t the case aesthetic encounters would be identical to a good story, an efficiently laid out, morally appropriate narrative to which each and every reader, listener etc. would have access and comprehend without second thought. In that case, what would we do about Stein, Brontë, Woolf, Beckett or Joyce? And who would be the judge of what good and appropriate is supposed to be? Some expert, from where in regard to what canon or tradition? We know very well who considers himself entitled to be the president of that jury.

Aesthetic encounters are not about stories but the opposite, they are not a matter of openness but about being open, and disinterested contemplation has nothing to do with accessibility or comprehension, but of being with, attending to something, without judgement, of being active yet indifferent.

Now, in the background a murmur: that’s easy, piece of cake, no problem, but give it a try, at the end of the day proper indifference is not just freaking difficult, it might even be humanly impossible.

In a late essay, “To Have Done with Judgement,” published in 1993, Gilles Deleuze proposes that judgement, even if in no more dramatic way than naming something, constitutes the world, and hence that indifference or disinterested contemplation implies a withdrawal, as we have seen, from judging. Judgement is not negative per se, obviously, it offers stability and continuity to relations, people, stuff, order and the world, but judgment, as Alexander Garcia Düttmann comments on Deleuze’s text, “is designed to prevent something new from emerging and new forms of life from constituting themselves.” Engagements with aesthetics implies Deleuze, referring to (predictably enough) Kafka, D. H. Lawrence and, of course, Antonin Artaud, is one of the very few experiences that carry the possibility of postponing judgment, or where judgment refers only to itself and not to a ground, power or, as Deleuze expresses it, to an eternal debt. Art is the domain par excellence where appreciation is not referential, it’s beautiful or I love it, needs no verification, or mustn’t require motivation, not from the individual or group that makes it or those who attend it.

Kant’s as well as Deleuze’s argument most certainly resonates with a modern project but instead of dismissing the line of thought right away let’s instead situate it in our present reality. If art and the engagement with art, is something that withdraws from judgement this implies that the experience, not the artwork itself but the experience isn’t charged with value. The aesthetic experience is not the experience of something, but following Deleuze, it’s the experience of experiencing, or the experience of liveliness, la vitalité.1

In a world where every millisecond, every square centimetre, every relationship is relevant only in regard to its value and cannot be otherwise since contemporary globalized capitalism knows nothing else, the aesthetic encounter, making and spending time with art, has become a space and temporality that doesn’t confirm the world as it is. The aesthetic, however, for obvious reasons doesn’t produce alternative, elaborate perspectives or propose solutions. What it offers is the possibility of an all together different sensation or thought to emerge, the possibility to start from a new beginning.

Art, proposed Boris Groys a few years ago, isn’t about making the world a better place, on the contrary art carries the capacity to make things come to an end. An end should just not be confused with simply destroying or breaking something but should rather be understood in the sense of the impossibility to continue like before. The aesthetic experience doesn’t give any directions but is irreversible, it suspends judgement and opens for the necessity of a paradigm shift, a change not in degree but kind.

*

Stories create worlds and worlding, imagining other possible or alternative worlds, has since a while been en vogue, the problem, however, remains, those worlds are created in the soil of conventions and knowledges that for centuries have authorised certain forms of power, violence, suffering, hierarchies and so on. Forms of knowledge that were not, but through dominance have been homogenized into becoming white, heteronormative, reproductive, colonial, oriented towards growth and property, in particular in regard to land, and so on.

Listening to the American thinker Fred Moten it is, at least in parallel, necessary to abolish worlds, or with the wording of Jack Halberstam to engage in processes of unworlding. Because, as Moten proposes the very idea of subjectivity is a human invention that has been used to colonialise every animate and non-animate capacity in the universe. So instead of worlding attempting to invent alternatives, unworlding embarks on a crusade against the very conditions that make any world possible. Said otherwise, worlding implies engagements in difference in the degree, which at best shakes the foundation of thought, value or being. After all, comparison (difference in degree) takes place in regard to a given grounds. It’s in fact precisely givens and grounds that need to be approached and this is what unworlding aims at, to, in Haberstam’s language “destroy” worlds as we know them in favour of all together other constellations (different in kind), that might or not be a world. Or as Halberstam proposes echoing Black thinkers such as Moten, Wynther, Gilroy, Baldwin, Spiller etc. black freedom requires the destruction of the world as we know it. And I like to add, that’s not just Black freedom but everybody’s and everything’s freedom.2

The question is just what exactly is implied using the word destruction, because after destruction we fix things, rebuild, restore and make sure conventions, rules and governments are reinstalled, and with that power structures, violence and the repressive machine we call language. Unworlding can neither be a question of tearing down, fucking things up, demolition derby, mass destruction or anything that has to do with objects, stuff, animals, societies, people or folks. What it must mean is destruction of nothing at all except structures or systems of thought, and those structures must be demolished in ways that are irreversible, ways that make rebuilding absolutely impossible. Unworlding implies to suspend judgment, to bring openness to an end and create the possibility for moments of being open, unconditionally open.

Unfortunately, Jack Halberstam, ends up twisting the argument of unworlding in an odd manner, unable to halt his arguments before asking the question, for whom? The moment unworlding implies an address when its process gains direction and becomes valuable for somebody or many, unworlding folds in on itself and becomes worlding. In order to suspend judgement unworlding must remain indifferent, must never become a story and remain an open landscape.

- La vitalité, is sometimes translated vitality and something liveliness. The English translation of Deleuze text uses vitality whereas Düttmann quoting the French edition, translates la vitalité to liveliness. I use liveliness due to the possibly unnecessary context in which vitality can be used, connotations that are not, at least not to the same extent, attached to la vitalité.

- Everybody’s and everything’s freedom, in regard to that freedom, in any prominent sense, cannot be partial, a privilege for some, but must include everybody. Without relativising suffering, on a philosophical level, both the un-free and those that controls or police freedom, although differently, are un-free relatively a constitution or system. Differentiating between constituted freedom and prominent freedom, freedom without conditions, Moten along with Halbergstam cannon not argue for forms of freedom without conditions, which in Moten resonates with the concept of the undercommons.

2 December 2023

I Will Always Love You

Dolly Parton wrote the song ”I Will Always Love You” as a farewell to her business partner and mentor Porter Wagoner. It was a great song when it came out in 1974, sang with a genuine Parton vibe, after all, she wrote it and performed it. It was her emotions, her goodbye.

In 1992 Whitney Houston recorded the song in connection to the film The Bodyguard, and the soul-ballad version became a super hit. It’s strange though, at least to me Whitney’s version is something else, deeply touching and irreversible, which is paradoxical because, it’s not her words, her harmonies, her feelings, her departing from a loved one. Still, I cry, every time.

Jacques Rancière writes about dissensus in art and politics, proposing that dissensus, in fact, isn’t a conflict, a dispute between two identifiable entities where one is more likely to win. It’s not a form of antagonism in line with Chantal Mouffe, but instead a productive tension between, as he words it, sense and sense. Between “sensory presentation and a way of making sense of it” or, in day-to-day language, between how something is experienced and how it is given meaning. Consensus, which isn’t something negative but instead absolutely necessary in order to conduct life, occurs when sense and sense, experience and meaning, fit together or coincide when there’s no leakage in either direction.

Mind you, the French philosopher doesn’t exemplify with Whitney Houston, but perhaps what makes the difference between her and Dolly Parton’s versions is precisely that in regard to the original version, there’s consensus between this and that, whereas in the remake rather than creating a sense of estrangement or simply coming across as superficial, the leakage between experience and meaning is what creates the possibility to get emotionally carried away. Or, actually not emotionally, what surfaces is sensation or affect, and the difference is that emotion is something that can be identified and located whereas affect is sensed but cannot be identified, named or located. Dolly Parton’s version of “I Will Always Love You” is surprising but conventional, and Whitney’s, not least because it’s a cover, is ordinary yet overwhelming. Or, Parton: Oh wow but it’s just a love song, and Houston: It’s just a pop song but oh wow, and where wow, or whatever the exclamation, never lands, it just continues to wow even though it’s nothing else than a cover version of a commercial hit.

In an interview available on Youtube, another French thinker, Jacques Derrida, asked to reflect on love, differentiates between who and what one loves, between the absolute singularity of who the person is and the qualities, the beauty, the intelligence, the economic value of the person. The heart of love is divided into the who and the what. Love is an engagement with, however, Derrida isn’t using the term, the dissensus between who and what, between sensory presentation and the way it’s given sense.

I wonder what Jacques Rancière thinks about people that use sentences such as let’s agree to disagree. In regard to dissensus isn’t that precisely to transform a productive tension into a thing, something that can be located and identified, or in other words, let’s agree to disagree is enforced artificial consensus? Dissensus, perhaps similar to twilight or dusk, can only be identified through its negative, not simply in the sense of what it’s not, as that tends towards opposition, juxtaposition or contrast, and certainly not in respect of lack or absence. Twilight nor dissensus isn’t some kind of psychoanalytical backyard, on the contrary, it’s a stretched moment that although extended remains unframed and hence recalcitrant to image and technologies of capture. Dissensus is that immaterial extension that simultaneously is and isn’t between day and night, and that constantly withdraws from caption.

In “Bergsonism,” from 1966, Gilles Deleuze, today’s third French philosopher, differentiates between false and real problems. The first category is problems to which there exists a catalogue of solutions. It’s just a matter of making the right choice and every choice is obviously attached to value. Possibly this, or possibly that, in short, it’s a matter of probability, and even if there’s no final solution false problems confirm us as human beings, precisely because to overcome the problem demands nothing else than a bit of negotiation.

The real ones, on the other hand, are problems to which there are no solutions, that don’t offer choices, that cannot be negotiated. To which there’s no possibly this or possibly that. Real problems don’t operate in the realm of probability and are even beyond the sphere of imagination.

Evidently, it’s impossible to produce, to make, a real problem, neither can we look or search for them because they don’t exist as such. A produced or manufactured problem cannot not offer a solution of some kind. From Deleuze perspective, one can only produce the possibility for the emergence of a real problem, and it goes without saying that a real problem is intimately related to Jacques Rancière’s notion of dissensus. Real problems similar to dissensus have no direction and are indeterminate, still, it’s dissensus and real problems that generate prominent change in the world. Like affect, they cannot be located or pinned down, indeed a real problem is the emergence of dissensus.

In continuity, false problems, consensus, can orchestrate, as Deleuze proposes, change or difference in regard to degree, but only real problems, dissensus, can generate possibilities of difference in kind, and difference in kind operates outside the domain of possibility but instead in the realm of potentiality, that is, a dynamics that also includes what lies beyond the reach of language.

Between Dolly Parton’s and Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You” a conceptually crucial moment occurred, the publishing of Judith Butler’s “Gender Trouble,” on the 1st of March 1990. In her seminal book, the American scholar connects J.L. Austin’s theories of performativity with Jacques Derrida’s proposition that language in itself is performative and elaborates the world-changing idea that identity, and not just human identity but anything’s identity, is performative and prominently situated, or made possible through language.

Judith Butler convincingly unpacks the impossibility of a static, singular and personal identity on several layers. If language is how humans have access to the world, identity cannot not be constructed through language, and if language is performative, in other words, that it has no foundation but is constantly changing, there can be no proper stability to identity. A radical aspect to Butler’s thought is that a person’s identity is never personal but engineered or constructed through shared conventions. There is no real you, no true self to find underneath your skin. Identity is performative, constructed by each of us in collaboration with the world in an ongoing process, which of course means that our identity changes depending on context from daughter to mother, professional, lover, performance artist, dog owner, New Yorker, single and millions of other opportunities. You are never you but always they, forever plural, and by the way you are never but are constantly practising all those overlapping identities. To be someone after all refers to a stable entity. Identity politics eradicated being.

Just in order to underline. If language has no foundation, truth, in any radical sense becomes impossible. Truth is dependent on a firm foundation, on some or other form of index, and hence there something like a true self becomes an anomaly, and even if there could be a true self, as humans we cannot gain access to it, precisely because it exists outside the realms reachable through language. We should, however, remind ourselves that this fact is a blessing since a true self is absolutely static and as boring as contemplating the universe or dad jokes.

*

Returning to Dolly and Whitney, in Parton’s version, from the early 70s, it’s a stable form of identity that performs the song and hence her love can be true, which is perhaps why she can or had to, perform it without baroque exaggerations. In the case of Whitney, the name of the game is altogether different, to her it’s all about how she performs the song because there’s nothing real only a matter of appearing convincing, to Whitney’s love there’s no truth.

The importance of Judith Butler’s articulation concerning performativity and by extension the rise of identity politics cannot be overestimated. Although in the shadows, it has revolutionized the world, perhaps both for the good and the bad. Not only did it give traction for entirely new forms of struggle and opportunities for minorities of different kinds, in particular women, people of colour and sexual minorities, it also paved the way for entirely new ways of comprehending what it implies to be human, even what a human is. Interestingly, the advent of the so-called performative regime coincided with new forms of individuality geared through neoliberal capitalism that could take on globalised economies the moment the cold war ended in 1989. Not only were Butler’s concepts brilliant the timing was also immaculate and in hindsight appears tailored for the moment.

A performative identity contrary to a classic static understanding of the I, business understood can be improved and it becomes up to each and all of us to invest in ourselves. As proclaimed in the influential and provocative book “The Coming Insurrection” by The Invisible Committee from 2007, we had no choice but to understand that today and into the future our most precious property is not your yacht, luxury villa or car but your identity. What you sell is you and how affordable respectively investible you are, which includes dress code, what Pilates studio you visit, if you’re vegan, prefer wine in front of beer, what’s on your playlist, if you make activist art or not, dress up or down, solve sudokus, read Sally Rooney or carry a copy of John Cage’s “Silence,” and so on.

In the early 2000s, performativity became a watchword in art contexts, not just in regard to performative arts but all over the place and every biennale, museum and literature festival needed to include something performative. It wasn’t only that dance at this time ended up in the museum but every kind of art was packaged as performative. Not seldom was performative used as an adjective, it’s a bit performative you know, as if that made something interesting or cool. At other times it was understood as quantitative as if something could be more or less performative. But sorry, your identity doesn’t become more performative because you dance a lot, walk with a bouncy step or exaggerate facial expressions. Everything in the world, including immaterial things, every things’ identity including chairs, cities, historical events, dance performances, doctor’s appointments and so on, are performative. The moment when something is in relation to something else, performativity is inevitable.

A somewhat neglected perspective on identity politics and how it constructs worlds is that it’s deeply human-centric, and, as a prolongation of post-structuralist theories of language, became occupied to an overwhelming degree with relations, with the twist that objects, things and stuff are allowed existence only in regard to relations, and not in themselves. With its phenomenological backdrop, for theories around performativity objects don’t exist.

If language is conventional and, so to say, is the world in regard to access, a question arises: can one practice forms of identity that aren’t already incorporated in language? Said otherwise, from the perspective of identity politics one can only “be” forms of identity that language allows one to be, which from the perspective of Jacques Rancière implies that identity can only be consensual, frictionless and without tensions. Every identity is a possibility, it’s possibly this or possibly that, it’s probabilistic and, however for some provocative, always confirming being human in ways we already are. Simultaneously, identity politics must denounce Rancière’s concept of dissensus because it proposes the possibility that language is not as everything, which irreversibly would crumble the authority of the performative regime.

As far as I can see and feel, identity politics moreover ends up having problems with love, if love has anything to do with what Jacques Derrida proposed – that it’s a struggle between who and what, because from the perspective of Judith Butler’s theories, there can be no such thing as a who, that’s absolutely singular and unique. The performative regime ends up dismissing who and is left only with what, a form of love that’s nothing special but simply a matter of convention and negotiation. If Derrida could whisper, I love you because I love you, because of who you are, Butler ends up concluding that she loves somebody because of his or her features, long legs, scholarly success or rich family, which to me is a pity concerning love.

If this is what happens with love it’s also what befalls identity politics’ relationship to art. Because theories of performativity cannot expand, without some structural issues in the domains of language, it must reduce art to its tangible effects, thus dismissing the dynamnics of affect, or call it magic, that Rancière names dissensus. Hence, it’s making art into instruments, or tokens in regard to social environments. It cannot comprehend art in any other way than in respect of signification, what it does or produces, and even worse in regard to conventional causal relations, it transforms art into matters of cognition, knowledge and reflection.

Identity politics cannot blurt out, I love this painting, but is constantly covering its own tracks with arguments for why and under what circumstances this or that art is valuable. One could even say that identity politics crosses out the realm of art, a realm that carries the possibility for an absolutely singular experience, incorporating art fully into culture. Art is certainly created in regard to some or other culture but that doesn’t mean it’s identical to culture. The difference is crucial, first of all in respect of notions of autonomy and second, equally importantly, in relation to quantifiable value.

In order for a moment of dissensus to emerge it’s imperative that it’s without value, that it’s non-locatable and withdraws from language. The aesthetic experience, the encounter with dissensus is without directions, it’s an effect without cause as Rancière has it, it’s a moment without identity and lastly, it’s not performative, it’s not relational but an encounter with an object, an object as such.

Yes, a painting performs painting, a dance performance is performing dance performance and there might be people performing the dance and all of them are identities and have endless relations to each other and the world, but the aesthetic experience is not performative, it’s not constructed, it’s not dividable and therefore not measurable, it’s absolutely singular, and exactly because of that, it’s not an experience different in degree but different in kind.

It is there, in between Dolly Parton’s song and Whitney Houston performing it, between what it means for a white American and an black American woman to voice I will always love you, between the impossibility of truth and the miracle of love, between identity politics and absolute singularity that dissensus resides. It is there where art’s autonomy for a short moment appear, there between day and night that truth can be sensed, where things are not what they seem and yet more real than ever before.

6 November 2024

The Making of Worlds

Many years ago in a small theatre, a brief conversation with the person next to me. I was on the edge of surprised when she, in her mid-thirties, made clear that she had nothing to with performing arts. Perhaps slightly prejudiced, but in particular as she wasn’t in company with a friend. She expressed that she didn’t come to the theatre – in this one the program was largely dance – to be entertained. As an audience member I have a responsibility to what I attend. It’s not like going to work or anything like that, she said, but an active practice and this activity, she continued, is like a contribution to the performance or at least the situation.

As the light in the saloon started to dim, she whispered, “I’m here to do something, not just receive, you know, something already chewed and ready to consume. That I can do in front of my screen, and if the people on stage think I’m here to have a nice time,” before the darkness settled, she tapped her temple with her index finger a few times.

It was quite uplifting to be let into my neighbour’s spectator’s philosophy, and however kind of tacky, I remember a close friend, for decades insisting that theatre, or art in general, never is a matter of pleasing. Interestingly my compadre Jan never continued his argument, he never told me or the world what performing arts were supposed to be, just not pleasing. Not challenging, asking questions, change or make the world a better place, not to be revolutionary, destructive, fashionable, trash, empowering, cynical, it was simply not there to please. Hope was definitely not an option. As an old school Marxist, Jan would never fall for the temptation of hope.

It didn’t matter or perhaps it was essential that art didn’t know what other than pleasing it was. But pleasing, no matter what, meant rocking the audience members into the slumber of consumption, of passively receiving already agreed upon opinions, conventions, norms, morals, ethics and politics.

The opposite of pleasing however is not theatre, dance and art that engages with urgent topics. Evidently urgency is already pleasing and something that it feels great to engage with.

Together we, me and Jan, categorically refused to talk about the audience, always only audience members, which we understood as single entities that must not be grouped together under any circumstances. The idea of the audience as a collective, that could be addressed as one, a group or community, was something we had exorcised after being acquainted with the Italian thinker Paulo Virno, who made a strong distinction between a multiplicity and a multitude, where a multiplicity is a number of individuals or entities that can be grouped, whereas a multitude consists of entities that cannot, that can only be addressed as singular individuals. A multiplicity is made up of entities that are different in degree, such as humans, mammals, pianos. There are differences but they are not different in kind, which is the case of a multitude.

In regard to a multiplicity, the price to pay for belonging to a group, however, is the absence of a personal or individual voice. As Virno proposes, what arises from the multitude is not voices but an undefinable complaintive murmur. Indeed, when a head of state addresses the people, what is overlooked is the individual. The people are one and the single person’s requirements is not, cannot and must not be taken into account. When performing arts play for the audience, it no longer consists of singular existences, with their specific needs and demands, but only of a grey mass of anonymous nobodies. It goes without saying that every multiplicity is hierarchical and power oriented. It cares for everybody but can’t see you, at least as long as you don’t break the law.

The multitude is not cheap either but the price to pay is reversed. Here the individual possesses a singular voice but has no social network, no community to hide within and people or community to belong to. The multitude is a lonely place, and mind you, if you break the law or somebody breaks you nobody will take notice. The law is on vacation.

Multi this or that is not more or less favourable but the difference is crucial and what they do in the world is fundamentally otherwise. Concerning the realm of governance, it is clear that multiplicity operates in the domain of politics, whereas revolution is the travel companion of the multitude, which, exactly because it’s incompatible to group, is incompatible with politics, in the sense that Jacques Rancière proposes, politics being the maintenance of the polis, the city state.

There’s evidently a practical complication connected to any form of multitude, as long as it’s understood through Virno’s rather radical perspective. A multitude cannot have extension in time or in space, considering that any extension implies the establishment of relations which catapults multitude into, spot on, multiplicity.

In the arts, perhaps in particular performing arts, the conditions are overlapping although not identical to the realm of politics, after all we are in the protected space of the theatre. In there the conventional understanding is that we, the audience members enjoy, possibly because the defined timeliness, the safe and confirming support given by a multiplicity, the audience. Many, perhaps even most, visit the theatre not for what goes on on stage but primarily to be part of and perform being the audience. Theatre as social ritual, and even though what happens on stage is challenging or provocative it’s still pleasing, because after all the multiplicity confirms the identity of the individual, who as we know have no voice, which also means that one need have no opinion about no nothing at all. Comfy!

Now, to circumvent pleasing what’s needed is not noise, conflict, violence, spit, blood, high tech, provocation, activism, crude politics, nudity or authenticity, but the construction of a situation that lures that individual spectator out of the multiplicity, that generates momentum or activity in the individual audience member to emancipate themselves from, so to say, the crowd, and thus generate a moment’s multitude.

*

Generally speaking, there are two models discussed in regard to emancipation. The violent version represented by the situationists and Guy Debord. In short: If you don’t emancipate yourself, we will make it for you. Brute force, and some 30-40 years later through Jacques Rancière, who understood that for a moment to qualify as properly emancipatory it cannot be designed, strategic or directional. If it is, emancipation is nothing more than general independence, and the connection to multitude flips over to multiplicity.